Over the years, Deep Ellum has meant a lot of different things to a lot of different people. As one of the first black business and entertainment districts in the area, as a haven for suburban alternative and punk fans half a century later, and in its present incarnation as a creative enclave for artists and entrepreneurs, Deep Ellum has embodied a certain determination of spirit that has kept it distinctive generation after generation.

The Beginning: Two railroads, some factories, and the rise of a community

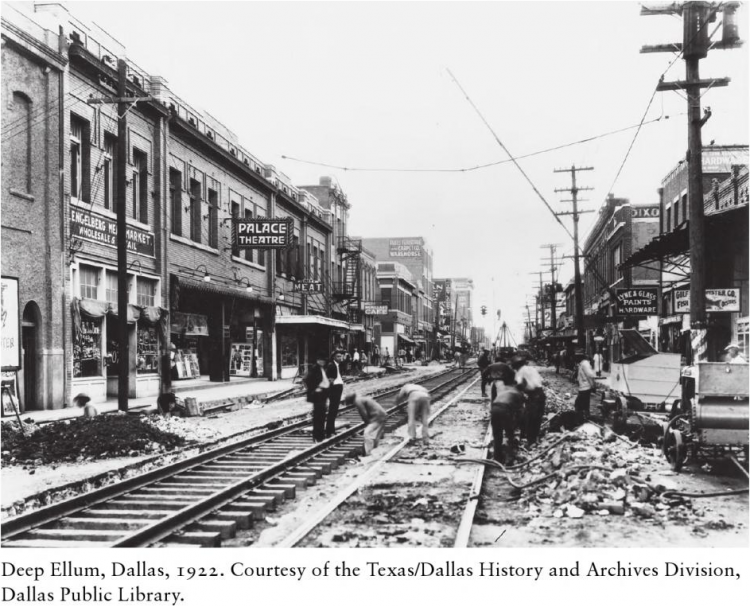

The area we know so well as Deep Ellum was first settled in the late 1870s as a “freedmen’s town”, populated primarily by former slaves, to be joined later by a smattering of European immigrants. It got its name from what is still its central road, Elm Street, and came quickly to be known as “Deep Ellum”, “Ellum” being the common pronunciation of “Elm” in the local dialect.

Folks were drawn to the area because of the presence of not one, but two railroad tracks, which offered some work and an opportunity to establish businesses that would serve the lines. At the time, what we now think of as one neighborhood was really two business districts, Deep Ellum and Central Track (on Central Street, which was then a railroad track), which were connected by a string of shotgun houses that formed a residential area called Stringtown.

At first, the whole area was part of a primarily African-American community consisting of several neighborhoods which together made up Old East Dallas. But in 1890, the City of Dallas annexed Old East Dallas, making it the largest city in Texas at the time.

By the late 1800s, the proximity of the railroads and of available workers made Deep Ellum a prime spot for industry, and it wasn’t long before the warehouses and factory buildings we see today started to be constructed. These included the Continental Gin Company building at 3309 Elm Street, which now houses a creative studio complex; a Ford factory built around 1914 that produced Model Ts; and the Knights of Pythias Temple, now the abandoned Union Banker’s building at 2551 Elm Street, designed in 1915 by the first black architect to operate in the state of Texas.

A 7th grader at Travis Middle School created a cool survey of some of the old buildings in the neighborhood, complete with histories and photos from then and now. Check it out on youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MSWfcMab3Aw

The Knights of Pythias Temple was significant not only because of its architect, but because it became one of the first professional buildings in the region to serve the black community, which still suffered under legally enforced segregation. At the Knights of Pythias building, black doctors, lawyers, journalists, and other professionals were able to provide services that the community had until then been largely without.

Among the notable professionals that began to populate Deep Ellum during this time was the wife of the Pythian Temple’s architect, Mrs. Portia Washington Pittman. Mrs. Pitman was the daughter of well-known educator Booker T. Washington and was also an accomplished musician. In addition to teaching private music lessons in the neighborhood of Deep Ellum, she also taught at the nearby Dallas Colored High School, better known now by its present name, Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. The school remains within walking distance of Deep Ellum, which has been a favorite destination of its students over the years.

The music: Blues, jazz, and a little honky tonk

As much as Deep Ellum had become a business district during the day, it became an entertainment district at night. And what is an entertainment district without a little music?

By the early 1900s, Deep Ellum was well known as the place to be for blues musicians from as far away as Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. Made famous by legendary residents like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, and blues pianist Alex Moore, Deep Ellum also frequently hosted performances by such iconic artists as T-Bone Walker, just starting his career, and Bessie Smith.

Starting with Blind Lemon Jefferson, Paramount records began signing recording contracts with Deep Ellum blues and jazz musicians, often using live recordings made right here at home. By 1950, the number of blues and jazz clubs in Deep Ellum had climbed to more than 20, from hole-in-the-wall dives to dedicated performance spaces like The Harlem and The Palace.

Accounts of Deep Ellum from the people who were there at the time tell of black artists and white artists playing together in unprecedented collaborations, of clubs filled with mixed-race dancing masses, of a cast of characters from pawn shop brokers to outlaws and gangsters. From the very beginning, Deep Ellum was a place where folk explored their own forms of expression, operating outside the mainstream and paving paths that would endure long after their creators had gone.

In 1985, The Dallas Museum of Art produced this awesome video of interviews with some of the musicians and patrons who frequented Deep Ellum in its Blues heyday: http://www.folkstreams.net/film,159

The End of an Era: The removal of the railroad, the building of an expressway, and a community moving on

After the end of World War II, Dallas began to look toward its future, which it saw in the sprawling suburbs to the north. Unconcerned with its inner city dwellers, Dallas’s city planners began constructing highways that would carry its more moneyed citizens from their jobs in the city to their homes in Far North Dallas and beyond.

In Deep Ellum, the Houston and Texas Central railroad tracks that had been the lifeblood of the neighborhood were removed to make way for Central Expressway. It soon became less and less practical for the residents of the area to remain, and many began to move to other parts of the city. Then, in 1969, a new elevation of Central Expressway eliminated completely the block of Elm Street that had held the majority of the venues that had fostered Deep Ellum’s vibrant music scene.

By the 1970s, little of what had characterized Deep Ellum until then remained. Vacated storefronts, abandoned warehouses, and empty streets were common sights. It seemed that what was once a rich and blazing community had been snuffed out by a highway. But under Deep Ellum’s abandoned streets and behind its dark windows, a spark still burned, one that was soon to be fanned into flame once more.

Photo credits:

- Knights of Pythias Temple (Union Banker’s Building) taken by Joe Mabel, courtesy of wikimedia commons Elm Street 1949 published on D Magazine’s Front/Burner blog January 15, 2014 as part of the “Ghosts of Dallas” series